Hole-in-the-Rock

The men were divided into five work groups: one to work at the crevice, one to build a road from the crevice to the river, one to build the ferry, one to cross the river and work on the Cottonwood Gulch road and another small group to herd the horses and cattle. With two blacksmith forges at the rim camp, the blacksmiths kept the tools sharp for drilling into the solid rock. Standing in half-cut barrels, the workers were lowered with ropes over the rim. Dangling in midair, they drilled holes in the cliff and filled them with blasting powder. In areas of sandstone, the holes were filled with water, and when the water froze, chunks of rock broke off. Not far below the first vertical drop of forty feet was another shear wall of fifty feet. Below this drop, the workers tacked a road to the cliff wall. This section of road was called Uncle Bens Dugway for the Welch miner, Benjamin Perkins. A narrow ledge for the inside wagon wheels was chiseled out along the wall. Below this narrow ledge, workers drilled holes every foot and a half parallel and about five feet below the ledge. The holes were two and a half inches in diameter and about ten inches deep. Cedar stakes from Kaiparowits Plateau were pounded into holes. Covered with logs and brush then rocks and gravel, the stakes provided the support for a wagon road; with only picks and shovels, the work was slow and tedious. Afraid of the deep dark crevice, the wagon teams had to be forced into the slot the first team down was a pair horses blinded by pinkeye. With the back wheels locked and up to twenty men and boys holding back with long ropes, the first wagon started down on the twenty-sixth of January. Jens Nielson's son-in-law, Kumen Jones is generally credited with driving the first wagon down. In his journal, Milton Dailey describes going down the Hole-in-the-Rock road: The first 40 feet down, the wagon stood so straight in the air it was no desirable place to ride. The channel was so narrow the barrels had to be removed from the sides of the wagon to let it pass through. Twenty-six wagons went down the first day. As the wagons went down the steep slope dirt and gravel was scraped off the road. David Miller claimed a chain tied around the blocked rear wheels dug in the ground. (Lee Reay claimed this was tried, but discontinued, the chain drug off to much dirt.) In places, the roadbed became like a toboggan run. On the steepest slopes, horses fell and were dragged, or pushed, but none of the horses were seriously injured. When Stanford Smith went back after his wagon, no one noticed him leave. He reached the top of the gorge alone. Smith left his children on the rim and drove the last wagon down with his wife and one horse tied on backwards to help hold back the wagon. His wife and the horse were dragged down the chute for about one hundred and fifty feet. Other than scrapes and bruises neither his wife nor the horse was seriously hurt. In small bunches, the cattle and horses were forced into the steep narrow Hole-in-the-Rock road crevice. One rider reported crossing the river twenty times before all of the cattle, oxen, and horses were swam across the river.

WillhiteWeb.com - Utah Sights

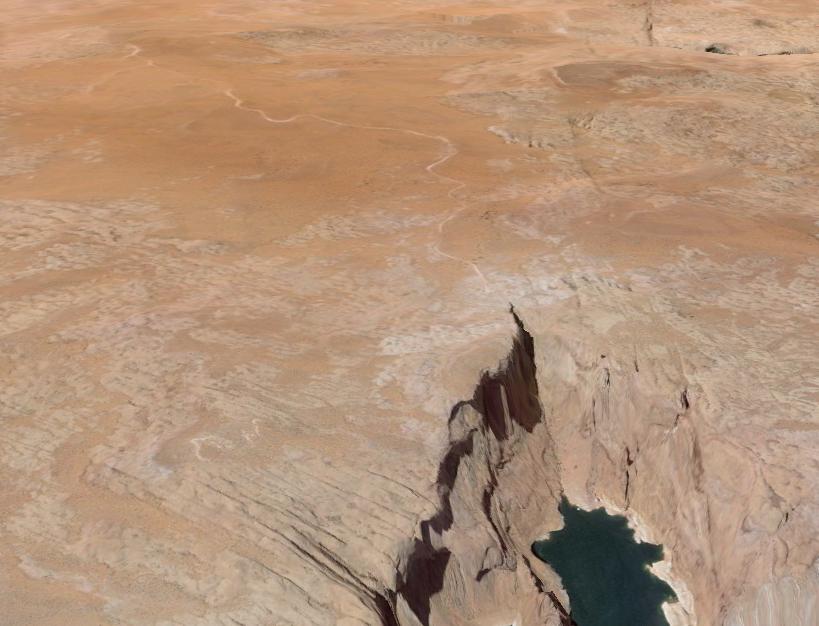

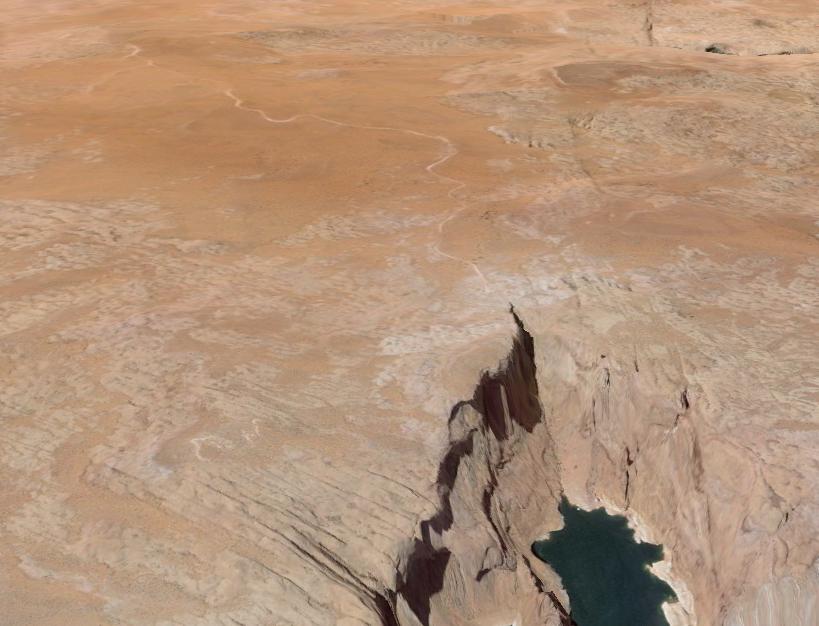

Google Earth view of the final few miles to Hole-in-the-Rock

Lake Powell

Looking up one of the drops

Looking up one of the drops

There is a boat down there

Looking down after dropping a few hundred feet

Hole-in-the-Rock from the top

Hole-in-the-Rock from the top

At the top parking area